What Can Philosophy Tell Us About the Eyewear Craze?

- Alejandra Rubio

- Feb 14, 2024

- 3 min read

From runways to TikTok filters, this phenomenon is so much more than a one-note trend.

One day you wake up with the belief that prescription glasses are worn to differentiate the brushstrokes from the visible world, and the next you find yourself digesting dozens of images of people turning this life-long necessity into an outfit-elevating accessory. We have seen it in Miu Miu’s Fall/Winter 2023 fashion show and through TikTok filters, making eyewear an undeniably explosive trend that has been spreading everywhere online throughout 2023 and into the new year.

How did this happen?

The answer brings us to the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the moment when millions of companies were forced to go from working in situ to relying on platforms like Zoom, which became an alternative to pure isolation. This technological dependence — including increased screen time — triggered, in some cases, early symptoms of myopia and eyestrain. It is no surprise that 19% of the British population has been wearing their eyeglasses more since quarantine. But why are we drawn to prescription glasses even when we don't need them?

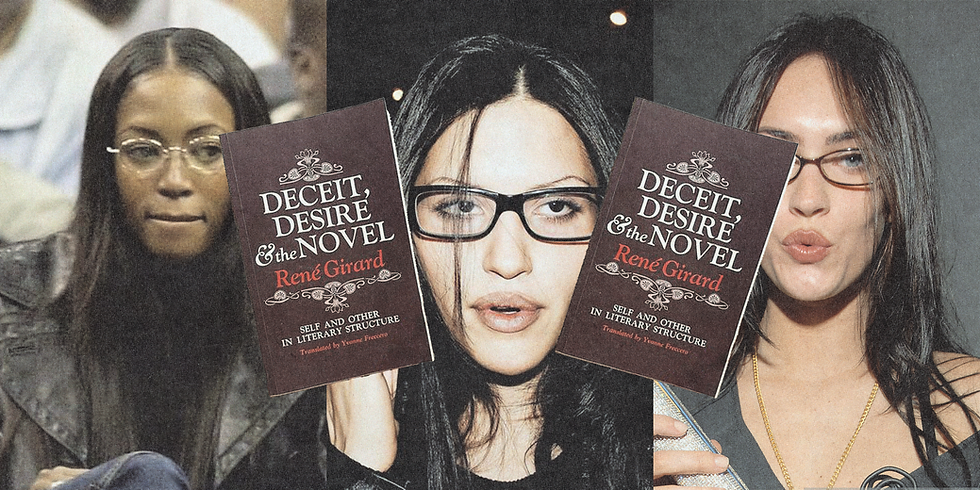

The French philosopher René Girard explains this in his mimetic theory of desire, first discussed in his 1961 book Deceit, Desire and the Novel: "Man is the creature who does not know what to desire, and he turns to others in order to make up his mind. We desire what others desire because we imitate their desires." Desire is a non-autonomous act and we are unaware of it.

This mimetic phenomenon is reduced to the learning process of animals and humans through the imitation of other members of a group. In this case, if one person desires, a second person sees and imitates the first person's desire, creating a passive conflict of that object. When the two factors mirror each other — for instance, models like Bella Hadid and Emily Ratajkowski wearing prescription glasses in public — any differentiation between them breaks this conflict by making the object in question look more valuable to bystanders. As a result, the need of some becomes the desire of others. That is why you might have, at some point, thought of trying on a pair of glasses that you would never have imagined putting on — or even needed in the first place.

On the other hand, the general inclination towards individualism — proliferated by the increase of second-hand shopping — has created a new wave in eyewear in which frames represent a nostalgic dream of the decades before the 2010s. We see it in internet sensations like Enya Umanzor with her oversized glasses and Gabbriette with the "Bayonetta" style frames, both being reincarnations of the 70s and the early 2000s fashion. This is indicative that the object is now evolving and adapting to all kinds of personalities and styles and still conserving the main ingredient of the mimetic phenomenon: the irrational desire to be part of the new wave of eyewear.

Will this become another passé concept of the 2020s?

If we rigorously follow the principles of Gerard's theory, we will find that the answer depends on the intensity and speed at which the object in question is acquired or normalized by the general public. We cannot deny the inevitable: once our desires are satisfied, or the object loses its value, we will look for the next source of stimulation that is considered unique and exclusive, taking us back to the beginning of the cycle of mimesis.

Who knows — maybe the next trend will be the antithesis of eyewear: colored contact lenses and, perhaps, eye surgeries. 🌀

Alejandra Rubio is a 23-year-old writer, programmer, and ancient soul who often analyzes and embellishes her surroundings through opalescent forms of self-expression. You can find her curating her visions everywhere online @glitched__girl.