Academia as Accessory

- Erica DeMatos

- Apr 9, 2024

- 4 min read

Updated: Apr 10, 2024

What does intelligence — or the illusion of it — offer us in fashion?

Intellectualism is in. JSTOR, the popular .PDF archive for students and academics alike, has become more than just a knowledge-sharing platform — it’s become a trend. And that trend has become representative of a major cultural shift away from last year’s embrace of the vapid “I’m just a girl” façade. Girls tweet about the .PDFs they save in Google Drive or are.na; they talk about how much theory they read; they even buy hats with Mary Gaitskill or Lydia Davis’ names embossed. The oversimplification of academic interests and accomplishments is a reductive and regressive attempt at seeming approachable, but can we say the same about the commodification of intelligence?

If trends are based, at least partially, on their perception from other people, there has to be some sort of external element that can be observed for them to be deemed valid, right? This externalization takes form in aesthetics, in labels, in the “-core” assignment as to what type of person you are. But if you’re into reading, how can you show this to people? How can you silently prove to everyone in the coffee shop that you like Joan Didion just as much as they do while you’re waiting on your almond milk cappuccino? The New Yorker (or The Paris Review, or Shakespeare & Company) tote bag is a virtue signal of one’s literary interests; with just a glance, everyone who looks upon your fashion accessory is aware that you care about academia. Or, at least, they know that you know it’s cool.

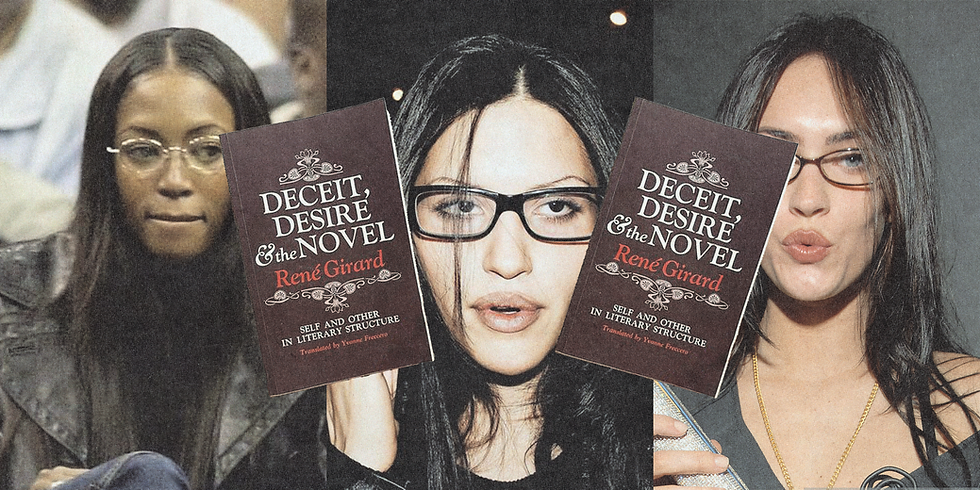

Model, actress, and famed nepo baby Kaia Gerber began a book club called Library Science in 2020, where she live streams to her 10 million Instagram followers while discussing books with guests from the likes of Jia Tolentino to Kaveh Akbar. Unveiling a deeper understanding of texts and relating to characters from fictional novels, Gerber proves to be both beautiful and smart, all at the same time. It makes sense: models are judged by their physicality, and through their physicality they must advertise what lies underneath. Paparazzi pictures of celebrities highlight this idea — that appearance and intellect are inextricably linked. Model Emily Ratajkowski, actor Jacob Elordi, and Gerber herself have all been photographed and lusted after on X for their dedication to the literary scene. They’re papped while wearing a quarterly magazine’s apparel or carrying a paperback copy of some feminist theory, providing voyeurs with a chimerical combination of beauty and brains. Regardless of intent — and whatever level of desire for social equity as a recognition of intelligence — hosting a free online book club for people all over the world cannot be a bad thing.

Wherever your feelings fall on the debate of intellect-as-accessory, it’s clear that this trend is a dissent from the feminist reclamations of recent years. 2022 presented hyper-feminization as a sort of social consciousness; self-proclaimed bimbos indulged in pink, glitter, Barbie, and any other stereotypical girlish aesthetics that were perhaps once used as a slight against women. Alongside this reclamation of innocent enjoyment, though, came the “girl math” trend of 2023: a new set of arithmetic propositions that suggest a lack of understanding toward what it means for a thing to have value and what it means to be hardworking. Girl math is needing your boyfriend to help add up the tip; girl math is ending up with a $20 Starbucks order. Priding oneself in being incapable of doing something correctly — and labeling it as something specific to the female experience — works against women’s fight for respect and independence. The bimbo-fied “girl math” seemed fun upon its initial adoption into the current zeitgeist, but it quickly became tired and destructive — and brought back a surface-level idea of equality amongst the sexes.

Susan Sontag speaks about the dangers of categorizing oneself in her 1966 collection of essays titled Styles of Radical Will:

“Ours is a time in which every intellectual or artistic or moral event is absorbed by a predatory embrace of consciousness: historicizing… The human mind possesses now, almost as second nature, a perspective on its own achievements that fatally undermines their value and their claim to truth. For over a century, this historising perspective has occupied the very heart of our ability to understand anything at all. Perhaps once a marginal tic of consciousness, it's now a gigantic, uncontrollable gesture - the gesture whereby man indefatigably patronizes himself.” (p. 74)

Confining oneself to the criteria of a certain aesthetic, or even a certain presentation of womanhood, is both limiting and consuming. Ever-present documentation of our corporeal being — and our engagement with the world — can become haunting when we try to develop our lives further. We know this to be true through our observations of interchanging fashion trends. How does this issue present itself when society not only turns to a new style, but also to a cultural, philosophical dissent? The constant self-consciousness around how we are perceived by others is pervasive and defining, making its way into the most minute of our clothing (and book) choices. People are complex, and so is our style of dress; we should not uphold a binary that limits self-expression and places womanhood in an anti-intellectual crucible.

I, for one, am happy to see some subversion of this reductive trend become popular. We seem to have adopted an aversion toward the pandering oversimplification of femininity. We’ve moved away from girlhood and into womanhood. The definition of the self has graduated from disguised slights to self-proclaimed intellect. But how long will it last? Let's hope that 2024 brings intelligence, beauty, and most importantly, earnestness — in our interactions with social media, each other, and ourselves. 🌀

Erica DeMatos is a writer, editor, and student based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Find her on social media at @erica_dematos.